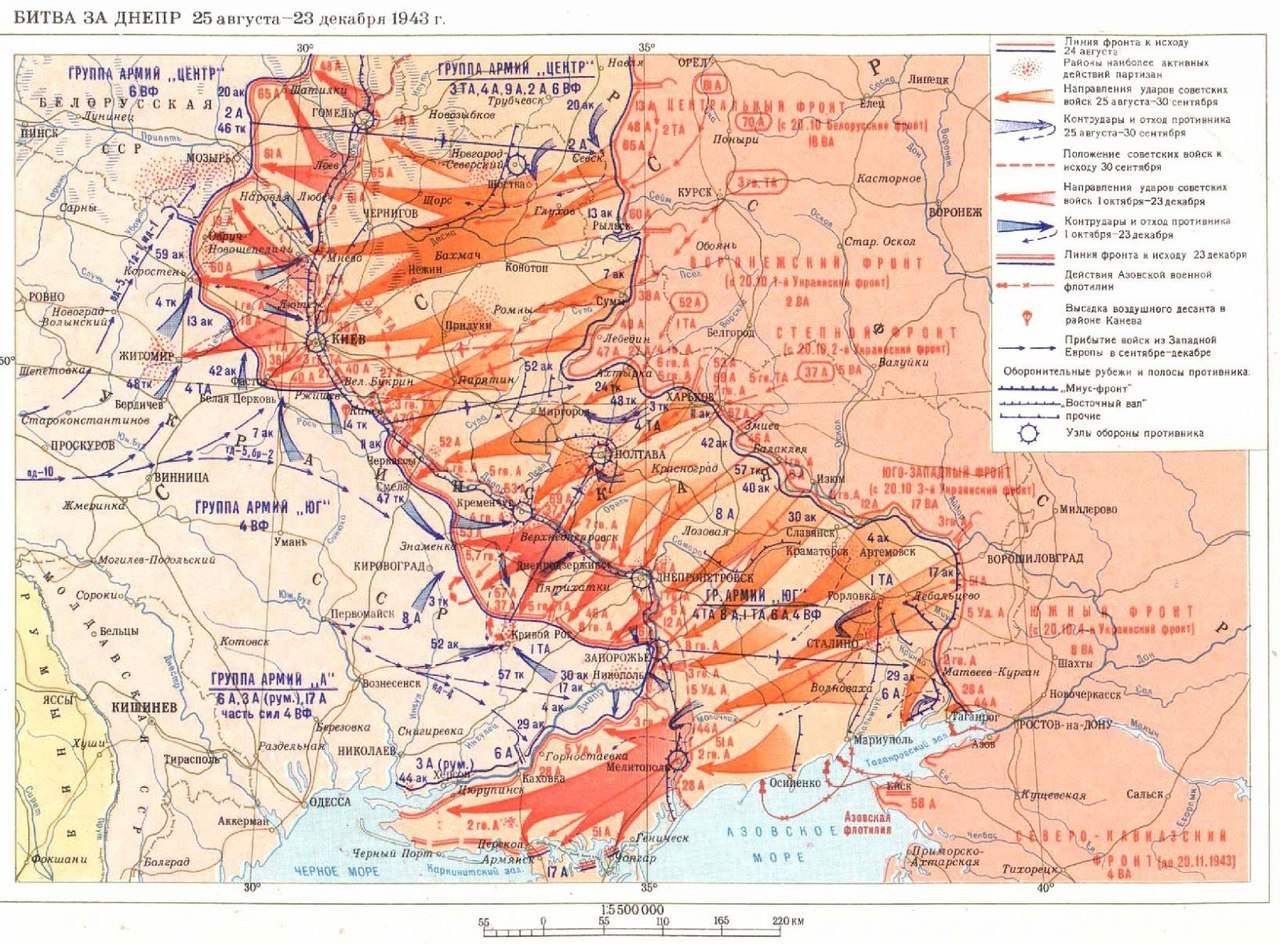

The Battle for the Dnieper is a series of interrelated strategic operations of the Great Patriotic War carried out by the Armed Forces of the USSR in the second half of 1943 on the banks of the Dnieper. Closely related to the battle for the Dnieper is the Donbas offensive operation, which was carried out simultaneously with it, which official Soviet historiography sometimes also considers an integral part of the battle for the Dnieper . To the north, the troops of the Western, Kalinin and Bryansk fronts also conducted the Smolensk and Bryansk offensive operations, preventing the Germans from transferring their troops to the Dnieper.

Before the battle

After the end of the Battle of Kursk, the German Armed Forces(Wehrmacht) lost all hope of a decisive victory over the USSR. Losses were significant, and worse, the army as a whole was much less experienced than before, as many of its best fighters had fallen in previous battles. As a result, despite significant forces, the Wehrmacht could only realistically hope for tactical success in the long defense of its positions from the Soviet troops. German offensives from time to time brought significant results, but the Germans could not translate them into a strategic victory.

By mid-August, A. Hitler realized that the Soviet offensive could not be stopped – at least until an agreement was reached in the ranks of the Allies. Therefore, his decision was to buy time by building numerous fortifications to contain the Red Army. He demanded that the Wehrmacht soldiers defend positions on the Dnieper at any cost.

On the other hand, I. V. Stalin was determined to speed up the return of the territories of the Union captured by the enemy. The most important in this regard were the industrial regions of the Ukrainian SSR, both because of the extremely high population density and because of the concentration of coal and other deposits there, which would provide the Soviet state with the resources it so lacked. Thus, the southern direction became the main direction of attack of the Soviet troops, even to the detriment of the fronts north of it.

Beginning of the battle

Preparation of the German defense

The fortifications on the right bank of the Dnieper, known as the “Eastern Wall”, began to be fortified by the Wehrmacht from August 11, 1943. After the defeat at the Kursk Bulge, it was the Eastern Wall, according to Hitler’s plan, that was supposed to stop the advance of the Red Army to the West.

Soviet offensive on the left bank

On August 26, 1943, Soviet divisions began moving along the entire 750 km front stretching from Smolensk to the Sea of Azov. It was a large-scale operation that involved 2,650,000 people, 51,000 guns, 2,400 tanks and 2,850 aircraft, in five fronts :

- Central Front(renamed Belorussian Front on October 20)

- Voronezh Front(renamed 1st Ukrainian Front on October 20)

- Steppe Front(renamed 2nd Ukrainian Front on 20 October)

- Southwestern Front(renamed 3rd Ukrainian Front on October 20)

- Southern Front(renamed 4th Ukrainian Front on 20 October)

In total, 36 combined-arms, 4 tank and 5 air armies were involved in the operations.

Despite the significant numerical superiority, the offensive was extremely difficult. German resistance was fierce – fierce battles were fought for every city and every village. The Wehrmacht made extensive use of rearguards: even after the withdrawal of the main German units, a garrison remained in every city and at every height, hindering the advance of the Soviet troops. However, by the beginning of September, in the offensive zone of the Central Front, Soviet troops cut through the German front and rushed to the Dnieper through the resulting gap. On September 21, they liberated Chernigov during the Chernigov-Pripyat operation.

Three weeks after the start of the offensive, despite the huge losses of the Red Army, it became clear that the Wehrmacht was not able to deter Soviet attacks in the flat, open space of the steppes, where the numerical superiority of the Red Army easily ensured its victory. Manstein requested 12 new divisions to help in the last hope of stopping the offensive, but the German reserves were already dangerously depleted. Years later, Manstein wrote in his memoirs:

From this situation, I concluded that we cannot hold the Donbass with the forces we have and that an even greater danger to the entire southern flank of the Eastern Front was created on the northern flank of the group. The 8th and 4th tank armies are not able to hold back the enemy’s onslaught in the direction of the Dnieper for a long time.

– Manstein E. “Lost Victories”. Chapter 15 Page 534.

As a consequence, on September 15, 1943, Hitler ordered Army Group South to retreat to the defensive fortifications on the Dnieper. The so-called “run to the Dnieper” began.

After defeats in previous operations, the German armies received the following tasks for retreating beyond the Dnieper:

- 6th Army to withdraw to the area between Melitopol and the Dnieper arc south of Zaporozhye;

- 1st tank in the area of Zaporozhye and Dnepropetrovsk;

- 8th Army to occupy fortified bridgeheads in the area of Kremenchug and Cherkasy;

- 4th Panzer to cross the Dnieper in the Kanev area.

If the task of the 6th Army was not difficult, then it was extremely difficult to transport the other three armies . The withdrawal of the German armies was accompanied by colossal losses in manpower, equipment and ammunition. Manstein states the following:

The group headquarters reported that in the three remaining armies, taking into account the arrival of three divisions still on the march, he had only 37 infantry divisions at his disposal directly for the defense of the Dnieper line with a length of 700 km, another 5 divisions that had lost combat capability were distributed between the rest of the divisions. Thus, each division had to defend a strip 20 km wide. The average strength of the division of the first echelonis, however, only 1000 (one thousand) people. After the arrival of the promised replenishment to us, it will be no more than 2000 people. It was clear that with such a manpower, a stable defense could not be organized even beyond such a border as the Dnieper. Regarding 17 tank and motorized divisions, the report stated that none of them had full combat capability. The number of tanks decreased as much as the personnel decreased.

The group headquarters reported that in the three remaining armies, taking into account the arrival of three divisions still on the march, he had only 37 infantry divisions at his disposal directly for the defense of the Dnieper line with a length of 700 km, another 5 divisions that had lost combat capability were distributed between the rest of the divisions. Thus, each division had to defend a strip 20 km wide. The average strength of the division of the first echelonis, however, only 1000 (one thousand) people. After the arrival of the promised replenishment to us, it will be no more than 2000 people. It was clear that with such a manpower, a stable defense could not be organized even beyond such a border as the Dnieper. Regarding 17 tank and motorized divisions, the report stated that none of them had full combat capability. The number of tanks decreased as much as the personnel decreased.

– Manstein E. “Lost Victories”. Page 576.

Such a situation with a shortage of ammunition, which was observed during the retreat, was not to be repeated.

– Manstein E. “Lost Victories”. Page 577.

Despite all efforts, the Soviet troops could not preempt the enemy in reaching the Dnieper. However, the German troops did not have time to take up a reliable defense along the western bank of the Dnieper. On September 21, they were the first to reach the Dnieper and the next day, the troops of the 13th Army of the Central Front in the Chernobyl region crossed it on the move. The next day, September 22, the same success was achieved by the troops of the Voronezh Front in the bend in the region of Veliky Bukrin.

To the south, a particularly bloody battle for Poltava unfolded. The city was well fortified, and the garrison defending it was well prepared. After a number of unsuccessful assaults, which seriously slowed down the advance of the Soviet Steppe Front, its commander, General I. S. Konev, decided to bypass the city and go straight to the Dnieper. After two days of fierce street fighting, on September 23, the Poltava garrison was destroyed. On September 25, the armies of the Steppe Front also reached the Dnieper.

So, by the end of September 1943, Soviet troops everywhere reached the Dnieper and captured 23 bridgeheads on it. Only the Nikopol-Kryvyi Rih bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Dnieper in the Donbass remained in the hands of the German troops. In the southernmost sector of the front, the opponents were separated by the Molochnaya River. However, the hardest battles were yet to come.

Dnieper airborne operation

In order to weaken resistance on the right bank of the Dnieper, the Soviet command decided to land paratroopers on the right bank. So, on September 24, 1943, the Dnieper airborne operation was launched. The goal of the Soviet paratroopers was to disrupt the approach of German reinforcements to the newly captured bridgeheads on the Voronezh Front.

The operation ended in complete failure. Due to the pilots’ poor knowledge of the area, the first wave of troops was dropped on Soviet positions and, in part, on the Dnieper. The second wave of 5,000 paratroopers was scattered over an area of several tens of square kilometers. Moreover, due to poorly conducted reconnaissance of the area, which did not allow detecting the mechanized units of the Germans, most of the landing, in the absence of anti-tank weapons, was suppressed shortly after the landing. Separate groups, having lost radio contact with the center, tried to attack the German supply units or joined the partisan movement.

Despite heavy losses, the Dnieper airborne operation diverted the attention of a significant number of German mechanized formations, which made it possible to carry out the crossing of troops with fewer losses. However, after the failure of the Vyazemsky and Dnieper landing operations, the Headquarters of the Supreme Command refused to continue the massive use of the landing force.

Forcing the Dnieper

Choice of action scenario

In the lower reaches, the width of the Dnieper River can reach three kilometers, and the fact that the river was dammed in some places only increased the possibility of its overflow. The right bank is much higher and steeper than the left, which only made the crossing more difficult. In addition to everything, the opposite bank was turned by the soldiers of the German army into a huge complex of barriers and fortifications, according to the directives of the Wehrmacht.

Faced with such a situation, the Soviet command had two options for solving the problem of forcing the Dnieper. The first option was to stop the troops on the eastern bank of the Dnieper and pull additional forces to the places of crossings, which gave time to find the weakest point in the German defense line and a subsequent attack in that place (not necessarily in the lower reaches of the Dnieper). Then it was planned to start a massive breakthrough and encirclement of the German defense lines, squeezing the German troops into positions where they would be unable to resist overcoming the defensive lines (actions very similar to the tactics of the Wehrmacht when overcoming the Maginot Linein 1940). This option, accordingly, gave the Germans time to gather additional forces, to strengthen the defense and regroup their troops to repel the onslaught of Soviet forces at the appropriate points. Moreover, this exposed the Soviet troops to the possibility of being attacked by German mechanized units – this, in fact, was the most effective weapon of the German forces since 1941. This scenario could lead to huge losses of troops, and, under certain conditions, to their complete encirclement and destruction, and then to the need to carry out the entire forcing operation again.

Faced with such a situation, the Soviet command had two options for solving the problem of forcing the Dnieper. The first option was to stop the troops on the eastern bank of the Dnieper and pull additional forces to the places of crossings, which gave time to find the weakest point in the German defense line and a subsequent attack in that place (not necessarily in the lower reaches of the Dnieper). Then it was planned to start a massive breakthrough and encirclement of the German defense lines, squeezing the German troops into positions where they would be unable to resist overcoming the defensive lines (actions very similar to the tactics of the Wehrmacht when overcoming the Maginot Linein 1940). This option, accordingly, gave the Germans time to gather additional forces, to strengthen the defense and regroup their troops to repel the onslaught of Soviet forces at the appropriate points. Moreover, this exposed the Soviet troops to the possibility of being attacked by German mechanized units – this, in fact, was the most effective weapon of the German forces since 1941. This scenario could lead to huge losses of troops, and, under certain conditions, to their complete encirclement and destruction, and then to the need to carry out the entire forcing operation again.

The second variant of the development of events was to deliver a massive blow without the slightest delay, and to force the Dnieper on the move along the entire sector of the front. This option did not leave time for the final equipment of the “Eastern Wall” and for the preparation of repelling the German side, but led to much larger losses on the part of the Soviet troops.

Soviet troops occupied the coast opposite from the German troops for almost 300 kilometers. All the few regular watercraft were used by the troops, but they were sorely lacking. Therefore, the main forces crossed the Dnieper using improvised means: fishing boats, improvised rafts made of logs, barrels, tree trunks and boards (see one of the photographs). The big problem was the crossing of heavy equipment: in many bridgeheads, the troops could not quickly transport it in sufficient quantities to the bridgeheads, which led to protracted battles for their defense and expansion and increased the losses of Soviet troops. The entire burden of forcing the river (as well as the entire Great Patriotic War) fell on the rifle units.

Forcing the crossing

The first bridgehead on the right bank of the Dnieper was conquered on September 22, 1943 in the area of the confluence of the Dnieper and the Pripyat River, in the northern part of the front. Almost simultaneously, the 3rd Guards Tank Army and the 40th Army of the Voronezh Front achieved the same success south of Kiev. September 24] another position on the west bank was recaptured near Dneprodzerzhinsk, September 28 – another near Kremenchug. By the end of the month, 23 bridgeheads had been created on the opposite bank of the Dnieper, some of them 10 kilometers wide and one to two kilometers deep. In total, by September 30, 12 Soviet armies crossed the Dnieper. Many false bridgeheads were also organized, the purpose of which was to simulate a mass crossing and disperse the firepower of German artillery.

From an eyewitness account of a reconnaissance tanker:

On the eve of the crossing, my commander approached me and asked if I would go. The answer that of course I would go, just to sleep off after two sleepless nights, caused him surprise. At first, 3 light tanks were thrown across the Dnieper on rafts, one of which I commanded. We did not climb up the hill. The tanks were camouflaged. This apparently saved our lives. A little later, the bombardment began. The Germans bombed the heights…

For his courage and heroism, the commander was awarded the Order of Bogdan Khmelnitsky.

After that, the Soviet troops practically created a new fortified area on the conquered bridgeheads, actually digging into the ground from enemy fire, and covering the approach of new forces with their fire.

The partisans provided significant assistance to the Soviet troops during the crossing of the Dnieper: in total, 17,332 Ukrainian Soviet partisans took part in the Battle of the Dnieper, who attacked units of the German troops, conducted reconnaissance, and served as guides for the crossing units of the Soviet troops :

Bridgehead defense

German troops immediately counterattacked the Soviet troops, who crossed to the right bank of the river, trying to throw them into the Dnieper. Aviation and artillery of the enemy inflicted continuous strikes on the crossings, sometimes making it impossible to cross the river, deliver ammunition and take out the wounded in the daytime. The Soviet troops, operating on small bridgeheads, did not have heavy weapons at their disposal, suffered huge losses, experienced an acute shortage of ammunition, food and other types of supplies.

German troops immediately counterattacked the Soviet troops, who crossed to the right bank of the river, trying to throw them into the Dnieper. Aviation and artillery of the enemy inflicted continuous strikes on the crossings, sometimes making it impossible to cross the river, deliver ammunition and take out the wounded in the daytime. The Soviet troops, operating on small bridgeheads, did not have heavy weapons at their disposal, suffered huge losses, experienced an acute shortage of ammunition, food and other types of supplies.

So, the crossing near the village of Borodaevka, mentioned by the commander of the Steppe Front, Marshal Konev in his memoirs, was subjected to powerful artillery and aviation attacks from the enemy. German bombers almost constantly and with impunity bombed the crossing and the Soviet troops located near the river. Konev, in this regard, points to shortcomings on the part of the command of the 5th Air Army in organizing air cover for crossings and air support for units and subunits that crossed to the right bank of the river. Only the personal intervention of the front commander made it possible to organize the work of aviation properly, and Konev’s order to concentrate corps and army artillery in the area of crossingsprovided powerful artillery support to the Soviet troops on the right bank of the Dnieper and allowed to stabilize the situation on this sector of the front.

The crossing of the Dnieper by Soviet troops, the capture of bridgeheads on the right bank of the river and the struggle to hold them were accompanied by heavy losses. By the beginning of October, many divisions had only 20-30% of the regular strength of the personnel.

A direct participant in those events, an officer of the German General Staff F. Mellenthin wrote:

In the days that followed, Russian attacks were repeated with unrelenting force. The divisions that had suffered from our fire were withdrawn, and fresh formations were thrown into battle. And again, wave after wave of Russian infantry stubbornly rushed to the attack, but each time rolled back, suffering huge losses.

– F. Mellentin, “The Armored Fist of the Wehrmacht”, Smolensk, RUSICH, 1999 – 528 p. (“World at War”)

Nevertheless, the efforts of the Red Army were crowned with success – during the fierce battles that lasted throughout October, the bridgeheads on the Dnieper were held, most of them were expanded. On the bridgeheads, powerful forces were being accumulated to resume the offensive and liberate the entire Right-Bank Ukraine.

However, the most important thing was that the German command was forced to use the last reserves . So, by the beginning of the Nikopol-Krivoy Rog operation, six infantry divisions of the 6th German army, which occupied the first position, were only battle groups, in both tank divisions by that time there were only 5 tanks . 11 infantry divisions of the 4th Army by the beginning of the offensive on Kiev were equal in terms of personnel to regiments . The situation in the 4th Army forced the German command to transfer to it two tank, two motorized divisions, two infantry divisions from the 8th Army, which created the preconditions for the encirclement and defeat of German troops inKorsun-Shevchenko operation.

Right Bank Campaign

Capture of the lower reaches of the Dnieper(Nizhnedneprovskaya operation)

By mid-October, the forces assembled by the command in the area of the lower crossings across the Dnieper were already capable of launching the first massive attack on the German fortifications on the opposite bank in the southern part of the front. So, a powerful attack was planned on the front line Kremenchug – Dnepropetrovsk. At the same time, large-scale military operations and the movement of troops were launched along the entire front in order to divert German forces (and the attention of his command) from the southern crossings and from the Kiev area.

By mid-October, the forces assembled by the command in the area of the lower crossings across the Dnieper were already capable of launching the first massive attack on the German fortifications on the opposite bank in the southern part of the front. So, a powerful attack was planned on the front line Kremenchug – Dnepropetrovsk. At the same time, large-scale military operations and the movement of troops were launched along the entire front in order to divert German forces (and the attention of his command) from the southern crossings and from the Kiev area.

By the end of December 1943, the troops of the 2nd Ukrainian Front, during the Pyatikhatskaya operation, the Znamenskaya operation and the Dnepropetrovsk operation, created and controlled a huge strategic bridgehead in the Dnepropetrovsk – Kremenchug region, more than 300 kilometers wide along the front and in some places up to 80 kilometers deep. To the south of this region, the Soviet command carried out the Melitopol operation, which ended with the cutting off of the Crimean group of German troops from their main forces. All hopes of the Germans to stop the offensive of the Soviet troops were lost.

Kyiv offensive operation of 1943

In the central sector of the battle, in the strip of the Voronezh Front, events developed very dramatically. A shock grouping of the front was assembled at the Bukrinsky bridgehead. In October 1943, she went on the offensive twice in order to liberate Kyiv with a blow from the south. Both attacks were repulsed by the Germans. Then, by the beginning of November, one tank and one combined-arms armies, as well as several corps, were secretly withdrawn from this bridgehead and transferred to the Lyutezhsky bridgehead north of Kyiv. The blow from there was a complete surprise for the enemy. On November 6, Kiev was liberated and a second strategic foothold was created around it.

Attempts by the German command to liquidate it and return Kyiv were repulsed by Soviet troops during the Kyiv defensive operation. With its completion, the battle for the Dnieper is considered completed.

Results of the battle

The battle for the Dnieper was another major defeat for the forces of Germany and its allies. The Red Army, which Hitler intended to stop for a long time on the Dnieper, not only was not stopped, but in a short time on a wide front crossed one of the largest rivers in Europe and inflicted a serious defeat on the Wehrmacht and its allies, forcing the German troops to retreat along the entire front. The liberation of Kyiv, the capital of the Ukrainian SSR, was of great political and moral significance. Despite the fact that most of the territory of Right-Bank Ukraine was still under the control of the Wehrmacht, it became obvious that the complete liberation of the Ukrainian SSR and the withdrawal of the Red Army to the borders of Romania, Hungary, Slovakia and Poland was only a matter of time. The most important industrial regions of the Donbass and the metallurgical centers of southern Ukraine were liberated, vast territories with a population of tens of millions of people. Despite the great destruction, the restoration of the industrial enterprises of the Union immediately began, and a few months later, a rapid increase in the output of military products began in the liberated regions. And at the beginning of 1944, the Red Army began the liberation of the Right-Bank Ukraine.

In addition, the battle for the Dnieper clearly demonstrated the strength and power of the partisan movement. The “rail war”, carried out by Soviet partisans from September to October 1943, significantly complicated the supply of German troops, forced the enemy to divert significant forces from the front to protect and ensure their rear communications.

Heroes of the Soviet Union

See also: List of soldiers awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union for their exploits in the battle for the Dnieper

The battle for the Dnieper is characterized by examples of mass heroism of fighters and commanders. It is indicative that 2438 soldiers were awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union for crossing the Dnieper, which is more than the total number of those awarded in the entire previous history of the award. Such a massive award for one operation was the only one in the history of the war. The unprecedented number of awardees is also partly due to the directive of the Headquarters of the Supreme High Command of September 9, 1943, which read:

In the course of combat operations, the troops of the Red Army have and will have to overcome many water barriers. The rapid and decisive crossing of rivers, especially large rivers like the Desna and the Dnieper, will be of great importance for the further success of our troops. <…>

For crossing such a river as the Desna River in the Bogdanov area (Smolensk region) and below, and rivers equal to the Desna in terms of forcing difficulty, submit for awards:

- Commanders of the armies – to the Order of Suvorov, 1st degree.

- Commanders of corps, divisions, brigades – to the Order of Suvorov, 2nd degree.

- Commanders of regiments, commanders of engineering, sapper and pontoon battalions – to the Order of Suvorov, 3rd degree.

For forcing a river such as the Dnieper River in the Smolensk region and below, and rivers equal to the Dnieper in terms of difficulty of forcing the above commanders of formations and units to submit to the title of Hero of the Soviet Union

— Quote. based on the memoirs of I. S. Konev

Here are just a few of the many who received the title of Hero of the Soviet Union for the successful crossing of the Dnieper River and the courage and heroism shown at the same time (a complete list of Heroes of the Soviet Union for crossing the Dnieper is contained in the book: The Dnieper is a river of heroes. – Ed. 2nd, add. – Kiev: Publishing house of political literature of Ukraine, 1988):

- Avdeenko, Pyotr Petrovich – Major General, commander of the 51st Rifle Corps

- Artamonov, Ivan Filippovich – battalion commander of the 25th Guards Rifle Regiment of the 6th Guards Rifle Division of the 60th Army of the Central Front, Guard Lieutenant.

- Akhmetshin, Kayum Khabibrakhmanovich – assistant commander of a saber platoon of the 58th Guards Cavalry Regiment of the 16th Guards Cavalry Division, guard foreman.

- Astafiev, Vasily Mikhailovich – Guard Captain

- Balukov, Nikolai Mikhailovich – commander of a machine-gun company of the 529th rifle regiment of the 163rd rifle division of the 38th army of the Voronezh Front, senior lieutenant.

- Belyaev, Alexander Filippovich – Guard Colonel, early. headquarters of the 41st Guards Rifle Division.

- Budylin, Nikolai Vasilyevich – commander of the 10th Guards Rifle Regiment of the 6th Guards Rifle Division of the 13th Army of the Central Front, Guards Lieutenant Colonel.

- Gavrilin, Nikolai Mitrofanovich – Soviet officer, commander of the 2nd Rifle Battalion of the 212th Guards Rifle Regiment of the 75th Guards Rifle Division of the 30th Rifle Corps of the 60th Army of the Central Front, Guard Senior Lieutenant, Hero of the Soviet Union.

- Godovikov, Sergei Konstantinovich – platoon commander of the 1183rd Infantry Regiment of the 356th Infantry Division of the 61st Army of the Central Front, lieutenant.

- Dmitriev, Ivan Ivanovich – commander of a pontoon platoon, lieutenant

- Yeleusov, Zhanbek Akatovich – Guards junior lieutenant, machine gunner of the 25th Guards Rifle Regiment of the 6th Guards Rifle Division of the 13th Army of the Central Front.

- Zelepukin, Ivan Grigorievich – Guards Sergeant, Commander of the Department of the Mortar Company of the 202nd Guards Rifle Regiment of the 68th Guards Rifle Division.

- Zonov, Nikolai Fedorovich – guard lieutenant, commander of a sapper platoon of the 1st Guards Separate Airborne Engineer Battalion of the 10th Guards Airborne Division of the 37th Army of the Steppe Front. On the night of October 1, 1943, his platoon ferried the personnel of the 24th Guards Regiment across the Dnieper, and then participated in repelling enemy counterattacks on the right bank of the river.

- Kiselyov, Sergey Semyonovich – assistant platoon commander of the 78th Guards Rifle Regiment of the 25th Guards Red Banner Sinelnikovskaya Rifle Division of the 6th Army of the Southwestern Front, Guards Senior Sergeant.

- Kolesnikov, Vasily Grigorievich – company commander of the 385th rifle regiment of the 112th rifle division of the 60th Army of the Central Front, captain.

- Kombarov, Egor Ignatievich – Sergeant, 25th Guards Mechanized Brigade of the 1st Ukrainian Front.

- Kotov, Boris Aleksandrovich – mortar crew commander, sergeant

- Lobanov, Ivan Mikhailovich – squad leader of the 20th separate reconnaissance company of the 69th Red Banner Sevskaya Rifle Division of the 18th Rifle Corps of the 65th Army of the Central Front, sergeant.

- Lyudnikov, Ivan Ilyich – Commander of the 15th Rifle Corps, Lieutenant General. For the skillful organization of forcing and skillful control of the battle.

- Morkovsky, Veniamin Yakovlevich – private guard.

- Nikolaev, Vasily Semyonovich (April 3, 1907 – January 29, 1989) – machine gunner of the 5th Guards Mechanized Brigade (2nd Guards Mechanized Corps, 28th Army, 3rd Ukrainian Front) Guard Private, Hero of the Soviet Union.

- Pilipenko, Mikhail Korneevich – junior sergeant, intelligence officer, 1318th rifle regiment of the 163rd rifle division of the 38th army of the Voronezh Front, later lieutenant general of the USSR in the signal troops, colonel general of Ukraine.

- Ruvinsky, Veniamin Abramovich – colonel, commander of the 228th separate engineer battalion of the 152nd rifle division of the 46th army of the Southwestern Front.

- Tkhagushev, Ismail Khalyalovich commander of a rifle company of the 89th rifle regiment, lieutenant, Hero of the Soviet Union, the title was awarded on 10/25/1943, he was the first to cross the Dnieper River and attacked a height of 175.9 despite the enemy’s forces exceeding 3-4 times and occupied it, which ensured successful crossing of the remaining units of the formation and the Army.

- Fesin, Ivan Ivanovich – Major General

- Frolov, Ivan Yakovlevich (July 27, 1923 – 11/23/1992) – private, gunner of the 280th Guards Rifle Regiment (92nd Guards Rifle Division, 37th Army, Steppe Front)

- Sharipov, Fatykh Zaripovich – Senior Lieutenant, commander of a tank company of the 183rd Tank Brigade of the 10th Tank Corps of the 40th Army of the Voronezh Front.